by Howard Zinn

Theodore Roosevelt wrote to a friend in the year 1897: «In strict confidence . . . I should welcome almost any war, for I think this country needs one.»

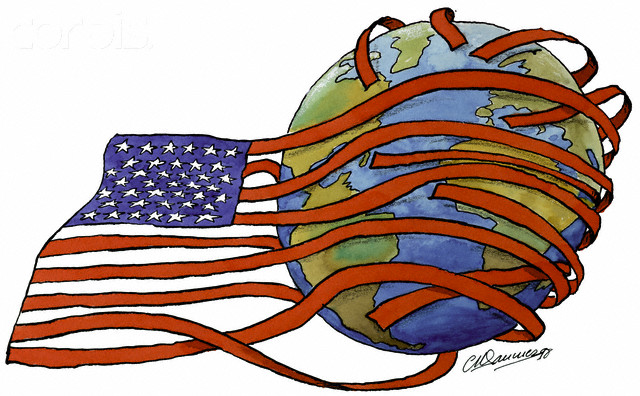

The year of the massacre at Wounded Knee, 1890, it was officially declared by the Bureau of the Census that the internal frontier was closed. The profit system, with its natural tendency for expansion, had already begun to look overseas. The severe depression that began in 1893 strengthened an idea developing within the political and financial elite of the country: that overseas markets for American goods might relieve the problem of underconsumption at home and prevent the economic crises that in the 1890s brought class war.

And would not a foreign adventure deflect some of the rebellious energy that went into strikes and protest movements toward an external enemy? Would it not unite people with government, with the armed forces, instead of against them? This was probably not a conscious plan among most of the elite — but a natural development from the twin drives of capitalism and nationalism.

Expansion overseas was not a new idea. Even before the war against Mexico carried the United States to the Pacific, the Monroe Doctrine looked southward into and beyond the Caribbean. Issued in 1823 when the countries of Latin America were winning independence from Spanish control, it made plain to European nations that the United States considered Latin America its sphere of influence. Not long after, some Americans began thinking into the Pacific: of Hawaii, Japan, and the great markets of China.

There was more than thinking; the American armed forces had made forays overseas. A State Department list, «Instances of the Use of United States Armed Forces Abroad 1798-1945» (presented by Secretary of State Dean Rusk to a Senate committee in 1962 to cite precedents for the use of armed force against Cuba), shows 103 interventions in the affairs of other countries between 1798 and 1895. A sampling from the list, with the exact description given by the State Department:

1852-53 — Argentina — Marines were landed and maintained in Buenos Aires to protect American interests during a revolution.

1853 — Nicaragua — to protect American lives and interests during political disturbances.

1853-54 — Japan — The «Opening of Japan» and the Perry Expedition. [The State Department does not give more details, but this involved the use of warships to force Japan to open its ports to the United States]

1853-54 — Ryukyu and Bonin Islands — Commodore Perry on three visits before going to Japan and while waiting for a reply from Japan made a naval demonstration, landing marines twice, and secured a coaling concession from the ruler of Naha on Okinawa. He also demonstrated in the Bonin Islands. All to secure facilities for commerce.

1854 — Nicaragua — San Juan del Norte [Greytown was destroyed to avenge an insult to the American Minister to Nicaragua.]

1855 — Uruguay — U.S. and European naval forces landed to protect American interests during an attempted revolution in Montevideo.

1859 — China — For the protection of American interests in Shanghai.

1860 — Angola, Portuguese West Africa — To protect American lives and property at Kissembo when the natives became troublesome.

1893 — Hawaii — Ostensibly to protect American lives and property; actually to promote a provisional government under Sanford B. Dole This action was disavowed by the United States.

1894 — Nicaragua — To protect American interests at Bluefields following a revolution.

Thus, by the 1890s, there had been much experience in overseas probes and interventions. The ideology of expansion was widespread in the upper circles of military men, politicians, businessmen — and even among some of the leaders of farmers’ movements who thought foreign markets would help them.

Captain A. T. Mahan of the U.S. navy, a popular propagandist for expansion, greatly influenced Theodore Roosevelt and other American leaders. The countries with the biggest navies would inherit the earth, he said. «Americans must now begin to look outward.» Senator Henry Cabot Lodge of Massachusetts wrote in a magazine article:

In the interests of our commerce . . . we should build the Nicaragua canal, and for the protection of that canal and for the sake of our commercial supremacy in the Pacific we should control the Hawaiian islands and maintain our influence in Samoa . . . and when the Nicaraguan canal is built, the island of Cuba . . . will become a necessity. . . . The great nations are rapidly absorbing for their future expansion and their present defense all the waste places of the earth. It is a movement which makes for civilization and the advancement of the race. As one of the great nations of the world the United States must not fall out of the line of march.

A Washington Post editorial on the eve of the Spanish-American war:

A new consciousness seems to have come upon us — the consciousness of strength — and with it a new appetite, the yearning to show our strength. . . . Ambition, interest, land hunger, pride, the mere joy of fighting, whatever it may be, we are animated by a new sensation. We are face to face with a strange destiny. The taste of Empire is in the mouth of the people even as the taste of blood in the jungle. . . .

Was that taste in the mouth of the people through some instinctive lust for aggression or some urgent self-interest? Or was it a taste (if indeed it existed) created, encouraged, advertised, and exaggerated by the millionaire press, the military, the government, the eager-to-please scholars of the time? Political scientist John Burgess of Columbia University said the Teutonic and Anglo-Saxon races were «particularly endowed with the capacity for establishing national states . . . they are entrusted . . . with the mission of conducting the political civilization of the modern world.»

Several years before his election to the presidency, William McKinley said: «We want a foreign market for our surplus products.» Senator Albert Beveridge of Indiana in early 1897 declared: «American factories are making more than the American people can use; American soil is producing more than they can consume. Fate has written our policy for us; the trade of the world must and shall be ours.» The Department of State explained in 1898:

It seems to be conceded that every year we shall be confronted with an increasing surplus of manufactured goods for sale in foreign markets if American operatives and artisans are to be kept employed the year around. The enlargement of foreign consumption of the products of our mills and workshops has, therefore, become a serious problem of statesmanship as well as of commerce.

Click on the following link to read the rest: http://www.historyisaweapon.com/defcon1/zinnempire12.html

Click here to read the United Nations’ Resolution 35 about Puerto Rico decolonization: https://infoaldesnudo.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/RESOLUCION-CE-PR-2016-1.pdf.

Click here to watch the video about the 2016 United Nations’ hearing on Puerto Rico decolonization: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=otzBslJLbI0

Click here to watch a video about how the US government made Puerto Rico its colony: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=36JhWdy3iYU&t=123s